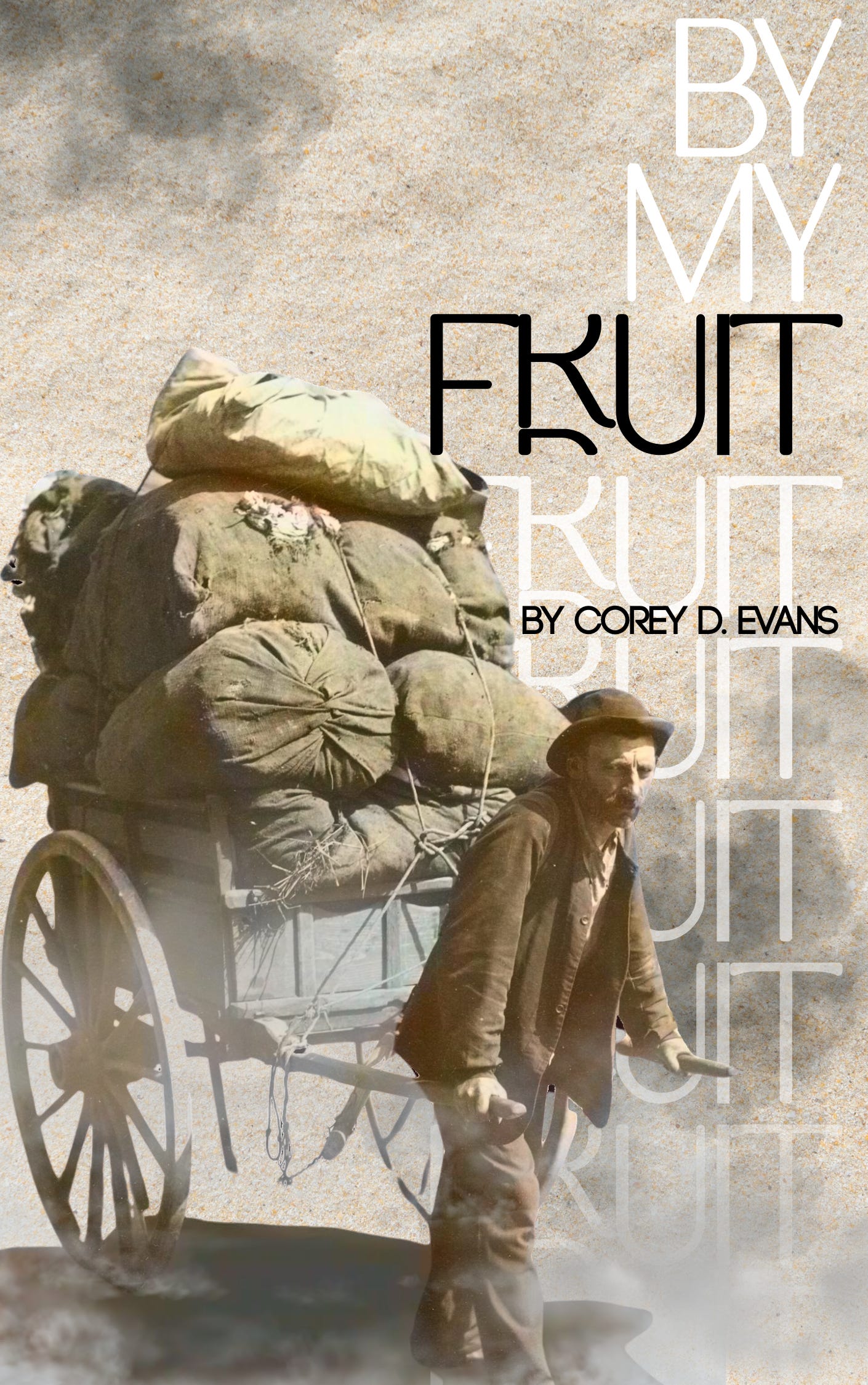

By My Fruit

A story to chew on

I’LL NEVER FORGET THE SUN THAT DAY I SHOT THE MISSIONARY. The first bright rays to break through the dense smog looked like white ribbons on brown paper. The brightest sun in over a month. I had to keep my head down because the light hurt my eyes. This made aiming my rifle all the more difficult, which is why he died the way he did. But I must explain a few things before I get to the trigger squeeze.

Of course, I didn’t know he was a missionary then. All I knew was a strange man came through the territory twice a month pushing a cart of meat. The smell of smoke-dried flesh preceded him by half a mile, and he’d holler, “Come get your protein,” when he thought he was getting close to those of us hiding under rock and sand. Gerald told me the farmers used to yell like that at markets back when there was enough food in the world to sell. Well, we didn’t have anything to pay him for the meat or even to trade for it. Most of us barely owned enough to cover the skin on our backs. Even still, while our stomachs actively digested our insides, none of us considered taking the offer. We were downright terrified of the man with the cart.

Timmons was the first to name our cause for fear.

“That’s long pork he’s got in the cart,” Timmons said after the man was out of sight. My twisted stomach groaned at the mention of the cart’s contents. “He’s trying to lure one of us into becoming the next meal,” Timmons said.

“Would that be so bad?” Gerald asked. There were three of us sheltered in the dugout, and Gerald was older than me by quite a few years. Old enough to have had a life before the end of everything.

“You wouldn’t want to be eaten,” Timmons answered as though he had personal experience.

“Don’t kid yourself,” Gerald said. “We all get eaten eventually. Some of us feed worms, others feed cannibals.”

“There’s not enough meat on your old bones to feed a worm,” I said. “Besides, we’ve already eaten all of them in this ground. You’ll just turn to dust when you’re gone.”

We laughed together and then Timmons said, “Bring your rifle next time he comes back.”

Gerald and I swallowed our humor. My rifle, an old, small-caliber varmint gun, was always by my side. I wore it across my back as we spoke about the cart. A firearm, even one without ammunition, was a valuable possession to have in the territory. I never took a chance setting it down out of arm’s reach. Timmons carried a pistol in his belt that I’m pretty sure wasn’t loaded. My gun was, but I didn’t have shells to spare.

“He’s not worth the lead,” I told Timmons.

“I say he is,” Timmons said. He looked at me hard with his thin, black eyes, but there was nothing more he could say. It was my gun and ammo, not his.

We watched the man pass by several more times after that. I always had my gun with me, and Timmons would tell me to take a shot.

“It’s just one bullet. He’s a sitting duck out there,” he said.

“He hasn’t done me any wrong,” I replied.

“Where do you think his cart full of meat comes from, huh? He’s got bits of people in there, man, and he’s trying to feed it to us.”

“It ain’t worth the lead,” was always my final answer before Gerald told us both to hush.

But things changed on the day the sun came out. The man with the cart passed back through the territory, and he wasn’t alone this time. A woman with black hair and dirty clothes followed behind the cart.

“Come get your protein,” echoed over the sands, and into the dugout. I thumbed at my rifle’s strap.

“Oh, come on,” Timmons groaned, “Now he’s trying to get us out with fresh meat?”

“Take the shot,” Gerald whispered to me. I looked at the old man. His pale eyes were almost blind but good enough to see my objection.

“We can’t watch this happen anymore. Take the shot.”

“If you don’t, I will,” Timmons said. I wheeled around to see him lift a hand towards the rifle at my back. He jerked away, and I looked back at Gerald.

“Are you sure? What if I miss?”

“You won’t,” Gerald said.

“Okay.” I took the rifle off and gazed narrow-eyed at the man pushing the cart. He was not a sitting duck. The man walked almost one hundred yards away from the dugout. A long shot for me. Every bullet I owned represented a full belly of game meat, and I only had ten shells left. I often went hungry rather than take a risk at closer targets; even a direct hit this time meant forgoing a meal in the future.

“I’m only taking one shot,” I told myself and the two men around me.

“You won’t miss,” Gerald encouraged.

I chambered a round and brought the wood stock into my shoulder. A headshot was out of the question, so I set the irons on the man’s back. Sun rays reflected off the sand and into my eyes. The mirage obscured my vision as the man took another step further away, and every moment of indecision brought the woman closer to being in the cart instead of walking behind it.

The shot rang out like a crack of thunder. The woman fled while the man screamed in agony. He fell to the ground, gripping his abdomen. A hit, but not a good one; my trigger pull was tense and sent the bullet down, to the right, and through the man’s liver. A fatal wound, but one that would take time to die from.

“Nice shot,” Timmons said with a grin.

“Shut up,” I said.

“You didn’t kill him,” Gerald said slowly.

“I did. He just hasn’t died yet,” I said.

“Take a second shot,” Gerald begged. He was looking at me again with that ancient stare of his. He expected mercy, but I was a harder man than him.

“It ain’t worth the lead,” I said and shouldered my rifle to end the discussion.

THE MAN TOOK HALF AN HOUR TO FALL SILENT AND DIE ALONE with the sand and the sun as his only comforts. I have no idea what happened to the woman, but she didn’t stay in the territory. She probably died somewhere on the road. It’s dangerous out there all alone. We watched the road for things to steal, but others were out there watching the road for something to eat. I’m sure she found a death not much different than what we thought the man with the cart would have dealt. A wasted bullet all around.

We left the dugout before the vultures came for the corpse. I told Timmons I didn’t want to patrol with him again, and Gerald told me the same. All of us were disgusted by what we’d done, or rather what I had done, and thought it best to part ways.

The days trickled by one after another like a fount of water running dry a gallon at a time. The sun hid behind the smog, and we did our best not to starve. I wouldn’t call what we had a community, but it was more than most had in the after— neighbors to help bury the dead instead of eat them.

It might have been a month or six weeks after I shot the man when a second pulling another cart appeared. This one snuck up on us. He walked as quiet as you could in front of a hand cart, and the smell of meat didn’t precede him. I and the other sentries barely made it into our holes before he came close enough to see us.

I peered out of the dirt dugout to see that this man wasn’t pulling a cart of meat but one of fresh fruit and vegetables.

“Oh, my god,” I couldn’t help but exclaim and lick my scurvy-ridden gums. I pulled my partner— a mousey, middle-aged woman named Jen— over to see what I saw.

“Does he have what I think he has?” She asked after looking through the peephole.

“I think I saw tomatoes,” I said.

The man with the cart came to his predecessor’s bones. Birds had picked them clean, and the world shrouded them in dust. A skull with empty eye holes looked up at the fruit man. Its jaw slack as if to say, “Nice to see you here.”

But the dead didn’t deter the man who bore fruit. He looked at the bones for a moment, then surveyed the dunes and sand embanking the road. He cupped a hand to either side of his mouth.

“Fresh fruit and veggies,” he shouted. I all but jumped at the sound of his voice. “Come out for food,” he yelled again.

“What should we do?” Jen asked.

“Ignore him,” I said, but then I spied one of the community emerging from their hole on the side of the road across from my dugout.

“Oh, no,” I huffed. I took off my rifle and stared down the sights at the man and the fruit. His smile was wide and beaming like a predator’s snarl. I chambered a precious round and adjusted my aim up and to the left.

“Don’t,” Jen whispered. She put her hand on my gun between the sights.

“Don’t?” I looked at her with the barrel still protruding through the peephole.

“Let’s wait and see.”

“They need cover,” I protested.

“Someone else can bear that burden,” Jen said. I disagreed— mine was the only loaded rifle in any direction— but I let her words prevail.

“Alright then.” I lowered my weapon while we watched the exchange.

It was Gerald who approached the stranger. He walked with his arms out, and the man with the cart returned the gesture. They greeted each other like scarecrows from neighboring fields. A show of good will. I couldn’t hear what was said. Eventually, the two men dropped their arms and came near enough to strangle one another if they wanted to. But the man with the cart began unloading bags of food at Gerald’s feet. More food than I could even imagine. Bags of potatoes and ears of corn, carrots, and tomatoes. A true miracle when every green thing you can recall eating came out of cans past their due by half a decade.

Gerald waved to the side of the road, and Timmons popped out of the earth like a prairie dog. The stranger backed away from his tribute of food while Timmons came near. He said a few parting words to Gerald, Gerald shook his head, and the man turned around. As he went, the empty cart made hollow, clattering noises on the weathered road.

Gerald and Timmons could not carry all of the food, so we came to help once the cart was well out of sight. I was the last to emerge from my hole after Jen. I walked towards the bounty with my gun still in hand. My companions smiled as each one sampled the goods.

“He said he’ll be back,” Gerald said over the revelry. “He said where he’s from has plenty of food to share, and we can follow him there if we wish.”

“Why don’t we follow him now?” Jen asked.

“He said we must be strong for the road ahead.”

“You mean he wants us fattened up for the slaughter,” I said.

“Perhaps,” Gerald sighed, but he looked unconcerned about this possibility. “Or perhaps people who can afford to give away food like this have no interest in our flesh.”

“What did he have to say about him?” I ignored Geralds’s remarks and pointed to the remains of the man I’d killed. The corpse was reduced to dun-colored bones in tattered clothes, bits of sun-dried flesh clinging around the joints.

“He said his name was Stephen,” Gerald said. “He said Stephen tried to give us goat’s meat.”

WE GATHERED TO EAT THE SUPPLIES THAT NIGHT. Gerald said the raw spuds needed to be cooked well, or the white flesh might kill us. He roasted the potatoes over a foul-smelling flame, but the odor could not deter our appetites. We ate the tomatoes while we waited. Their juices stained our filthy shirts and skin, and we looked like wild animals covered in the red flesh of our kill.

We were an odd group of misfits. I’m not even sure what brought us together originally except that we were all tired of fighting and killing when we gathered into a unit. I still wasn’t speaking to Timmons that night, but Gerald pulled me aside to talk after the potatoes were cooked near to crisps.

“That man today asked me if I killed the other,” Gerald said.

“What did you say?” I asked.

“I said I killed him.”

“Why did you say that?” I almost yelled. “What if he got mad and wanted to kill you?”

“ I did kill him,” Gerald said, “I told you to shoot him.”

“You know that’s not the same thing.”

“Would you have shot him if I didn’t tell you to?”

I stammered some excuse, but Gerald held up his hand for silence. His palms were old and withered. Too old. He was the oldest man I’d ever known, and I old enough to remember that that meant something, so I closed my mouth and let him speak.

“I killed him, son, I don’t want you thinking about it no more.”

“I don’t think about it,” I lied.

“Good,” he said. “Keep it that way.” Then he handed me the rest of his potato and slipped away into the dark.

TWO WEEKS LATER, the stranger returned. He didn’t call attention to himself or wait for anyone to greet him but unloaded his cart at Stephen’s feet and left. The third time he came, the cart was empty.

“Follow me,” he yelled into the wilderness. “Follow me to find salvation.”

“I’m going,” Jen said to me in our dugout

“Don’t,” I said.

“You should come, too.”

“I’m staying.”

“Okay then,” Jen sighed and walked out of the dugout. Others were already exposed and walking towards the stranger. He looked pleased at their number. There were a dozen of us in the territory. Eleven walked toward him now. I saw Gerald sweep the faces for mine and watched his head droop when he found me absent.

“Come and follow me,” the man cried once more, but those around him, those who knew me well, shook their heads. They knew I would not come, and soon, the man understood this, too. I watched them turn down the dusty road and leave me alone with the bones.

WHY WOULD A MAN LIVE ALONE AT THE END OF THE WORLD? Why press on when all around him is dead and gone? Is it because he understands that the universe demands a witness because he knows that when the last man is gone— when conscious thought flickers out— all else will cease to exist? I don’t think so. I think it is more simple than that. I think we’re scared of death and will choose to fight it down to the last man standing.

I was the last man, as far as I could tell. I often stood over Stephen’s bones for company in those lonely months. They were white like alabaster and pitted from weather and wear. Almost a year had passed since I shot him, and not a day went by that I didn’t regret pulling the trigger. Gerald didn’t kill anybody. I did, and nothing that old man said could change that.

I had ten bullets before. Killing Stephen brought me down to nine, and I used eight more in just as many months after everyone else was gone. I spent many days standing over the dead with my gun in hand and wondered if I was worth the lead.

I was doing just that— contemplating a one-way trip to join Stephen— when a voice called from behind me.

“He lived up to his name.” the voice said.

I wheeled around and leveled the rifle on the heart of the man behind me. It was the fruit man, except today, he had no fruit or cart.

“Why are you here?” I asked after a long moment passed between us.

“His name was Stephen, you know,” the man continued as if he didn’t hear my question. “There was a martyr named Stephen long ago.” The man didn’t look at the gun or at the dead beside me. He looked at me and into my eyes with something I’ve since come to know as compassion.

“What’s a martyr?” I asked

“A martyr is whoever gets killed when two beliefs decide only one can survive. It is what you’re about to make out of me with that gun of yours.”

“I’m not making you into nothing except bird food if you don’t start speaking straight,” I said. The man smiled at this, though I could see a tinge of unease in his face. A twitch of nerves.

“A martyr is someone who is killed for what they believe in,” the man said, “and to answer your first question, I’m here for you.”

“Eleven people not enough for your appetites?”

“We don’t eat people where I’m from.”

“Where are they then? Where’s Gerry and Jen?” The man’s expression fell, and I saw I struck through to something he didn’t want to say. I shook the rifle and made its hardware rattle. “Did you even ask their names?”

“I know their names as well as I know yours,” he said to the barrel of my gun. “Brother Gerald wanted me to come to you.”

“He ain’t your brother,” I said.

“I assure you, he is.”

“Why ain’t he here then?”

“He died.”

Those two words, a simple sentence, compelled me to close the distance between us and press the muzzle hard against his nose. I don’t think I broke it, but blood trickled down his face. I’m sure he didn’t mean to cry; you just do that sometimes when something hits you hard between the eyes, but tears mingled with his blood and made a mess of things on the road.

I roared words at him I’d rather not repeat and pushed little round bruises into his cheeks and chin. I had no right to bully him that way. If he wanted to, he could have easily overpowered me. I was emaciated and missing teeth from malnutrition. He was well-fed and much bigger. But he took my abuse and only resisted out of reflex. At one point, I had him down on his knees with my gun in his mouth.

“You ain’t worth the lead,” I said, slipping my finger on the trigger. Any other man would have done their best to fight away from the open barrel, but he spread his arms wide and looked at me with those damned compassionate eyes.

“You ain’t worth the lead,” I said again and turned the gun on myself.

The fighting spirit the man lacked before appeared like fast-moving storm clouds over the desert sands. He rose from his knees to sweep the rifle away from my face with the force of a gale and wrestled me down to the hot road. We both had hands on the gun between us, but neither could find the trigger for the press of our bodies against each other.

“You miss him?” the man grunted. “You miss Gerry?” I couldn’t look him in the eye, so I stared at one of the bruises on his chin.

“Don’t say his name,” I said.

“He had a lot to say about you,” The man said. I pulled at the gun but lacked the strength to break his grip. “He said you’re a good man and don’t deserve to be out here alone.”

“He did not,” I said.

“He also said you’re a mean son-of-a-cuss and won’t come with me unless I drag you kicking and screaming, but I think he was wrong about that.” The man gave the gun a mighty heave and ripped it out of my hands. I didn’t try to grab it back. I was weak, and he knew it.

“Go on. Kill me then,” I said. To my surprise, the man did not. Instead, he pulled the bolt back on the rifle and ejected the single shell into his palm. His hand jerked when the bit of brass and lead touched skin. I don’t think he was expecting the gun to actually be loaded. He looked at his hand, then at me with the respect one shows a snake in the grass.

“You got any other weapons on you?” the man asked.

“I got a knife,” I lied.

“Keep it,” he said, “and keep this, too.” He reached out to give me the bullet. I put my hand beneath his, and he dropped the bullet into it. It was warm from his touch and felt alive, heavy, and happy to be free from its chamber.

“I don’t got a knife,” I told him.

“That’s okay, I’ll get you one.”

“You don’t think I’ll try to kill you with it?” I asked.

“I’m not giving you that good a knife.” The man rifled through his pockets as he spoke and produced a scrap of sharpened iron wrapped with cords for a handle on one end. He handed it to me. The metal wasn’t much of a knife at all, but there was a point and a keen edge.

“It ain’t much, but a man needs a knife.”

“I could kill you with this.”

“You won’t.”

“How do you know?” I asked. The man looked me over, assessing me before he spoke again.

“Cause I know where Gerry’s grave is,” he said. The man turned back the way he came, and I chose to follow.

THAT WAS ONE YEAR AGO. The missionary took me to Gerry’s grave just like he said; the old man fed worms, after all. I buried my last bullet there with him. Could it have been the last bullet in the world? Probably not, but I swore to Gerry it would be the last one I’d ever touch.

After that, the missionary brought me here, to the Abbey. I healed. I learned to confess my sins and listen to sermons about love and grace. I learned that the missionary lied. You do eat blood and flesh here, but only that belonging to the Son of Man and not from men themselves. I took my first communion. I’m told Gerry did the same shortly before he died, which is why the missionary called him a brother and that he’s my brother now, too.

I also heard the talk about those living out in the West that are more like me: some mean sons of a cuss. I’ve listened to the whispers of the danger and have seen that no missionary who goes out to them ever returns.

Well, I can reach them. I think I can pull a cart into their territory and come out with a soul or two. If nothing else, I’m okay if I die trying. I don’t want to die. I’m not ready to go up to see Ol’ Gerry yet. But if what they say is true— that to die is gain— then what do I have to lose?

I’ll pull a cart past dry bones and cry out to those in the wilderness. I’ll call to those who are lost and weary: who kill those who they do not know.

But do not give me meat to carry. Give me an abundance of life to bear and not the sustenance from death. Let them know me by my fruit.

If you liked what you read, please share your support by buying me a coffee.

Short stories are published on a monthly basis. If you missed my previous story A Kiss of Magic, you can find it at the link below.

Copyright © 2026, Corey D. Evans. All rights reserved.

Thanks! It means a lot to get high praise from you 🤩

I really enjoyed this one. You really know when to zoom out and keep things cursory and when to sink into descriptions. Well done!