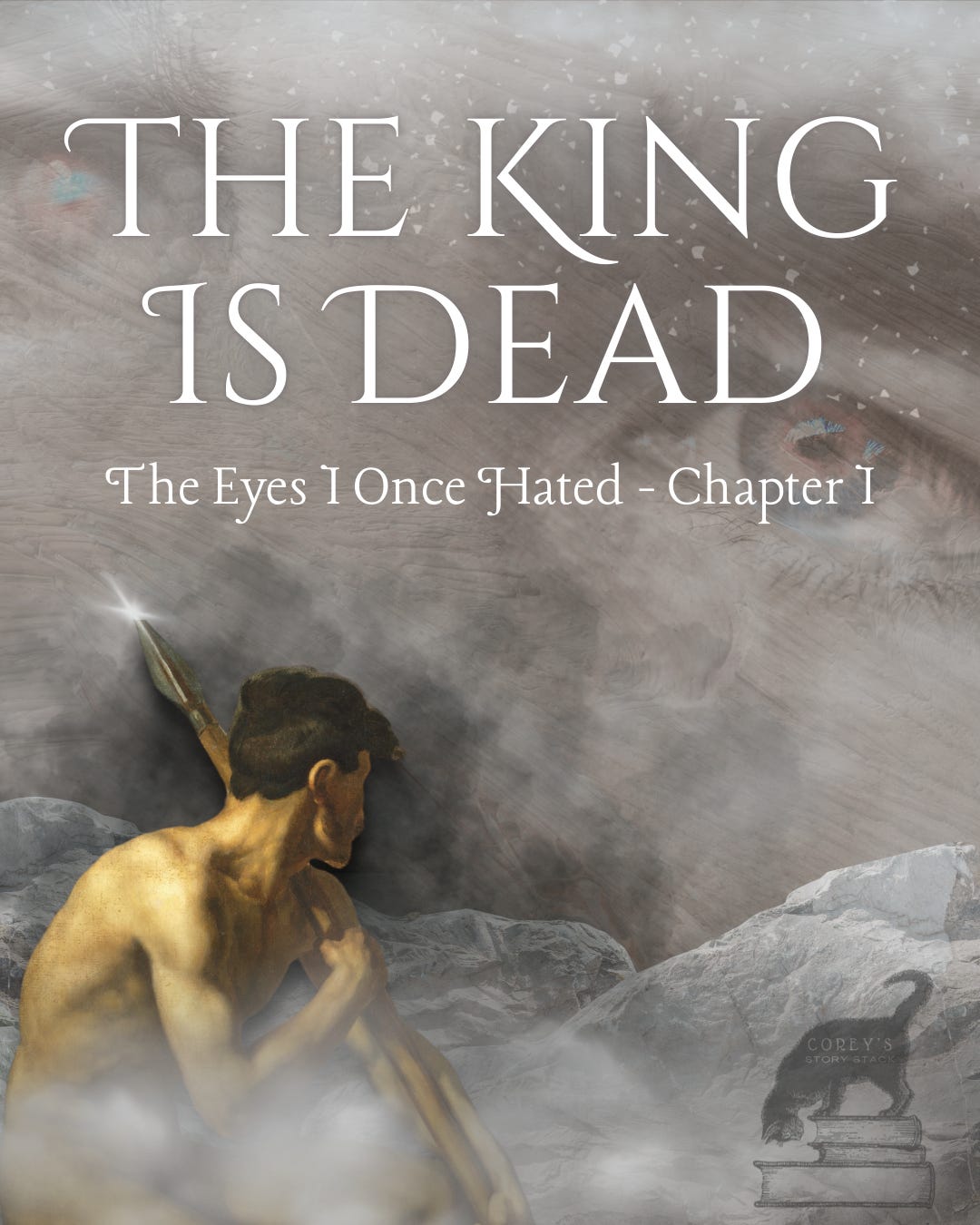

The King is Dead

In which a prince becomes a man, but not the king

HELP ME CHOOSE WHICH NOVEL TO SERIALIZE

What follows is the first chapter to my novel The EYES I ONCE HATED. It is one of two novels I am debating on serializing this fall (2025). Whichever excerpt collects the most engagement by the end of September will be the one I publish exclusively to Substack. If you would like to read more of this story, be sure to let me know by liking, commenting and sharing this chapter.

DAK STOOD OVER HIS FATHER’S BODY. The hounds tore at the carcass of the hunted boar and paid no mind to their dead masters in the thicket. The king's dark eyes remained open and stared unflinchingly into the sun. His final unspoken words caught on lips that would never close on their own again. There was no sign of pain or fear on the king's dead face. Dak had never seen fear in his father's eyes. Why would it be in them now in death?

The boy turned away and wretched. He had not eaten before the hunt, so only water and yellow bile fell to the earth. The acid sting clung to the back of his nose and throat, and his teeth felt fuzzy when he was done. It was not the sight of his father's blood that turned Dak's stomach, but the sudden realization of what also lay in the thicket beside the king: the bodies of five other dead or dying men cooling in the grass.

A cough brought Dak's attention away from the pool of his own vomit. The sound spun him around with the spear from his father's back raised and ready, but he was the only man standing in the thicket. Dak felled each one except for the king. He was in the midst of the hunting party running behind his father when he saw the spear of Ap'kalloo, the king's closest friend and ally, thrown into the monarch's back. Ap'kalloo and the other men on the hunt were too skilled for Dak to think that the throw was unintentional. These were the king's most trusted companions; kings and warriors who had allied themselves with his father and fought and bled alongside the man they betrayed. Four other spears turned on Dak before he fully understood what was happening, but he reacted to their betrayal quicker than they expected.

The men who sought to kill Dak were veterans of the fiercest battles, but the long years of peace under his father's rule made them soft and lulled their spear arms. They rarely trained for combat, whereas Dak's skills were fresh and well-honed. He drilled daily with the spear, and though he was only fourteen, Dak had ten years of untested combat training under his girdle. The fight unfolded like images out of a manual. The courtiers' spears each were true in their aim, but Dak's was faster.

The body that clung to life belonged to Yab-gal, the king's cupbearer. His chest was open to the gods above, but still his dying lungs found a way to take in breath. Dak approached Yab-gal with caution through mud made thick by the blood of six men. He thought he killed cleanly, but if Yab-gal lived, then there might be another lying among the dead still capable of putting up a fight.

The cupbearer coughed again. It was barely a gurgle and indistinguishable from the dogs' tumult over the body of the dead boar. Dak tried to ignore the sounds of the animals tearing into flesh, but his senses were raw from combat and tuned to every stirring in the thicket. If there was anything else left breathing, Dak would hear it. He examined each dead man for signs of life— a rising chest or twitching finger— as he approached the body of Yab-gal. He saw none, and even Yab-gal barely moved.

The bronze tip of Dak's spear came over the dying man. It glinted red in the sun like the angel of death itself. The blood of the king did not run easily from the tip, but congealed into a glistening mess that covered the bronze and some of the wooden shaft. Yab-gal could not turn his head toward the spear-wielding boy. He reached out to where Dak stood, but his arms flailed in the dirt instead. The strength in his body bled into the ground with each fluttering beat of his failing heart.

Dak watched the dying man take in a shallow breath before he drooled out another choking cough. The boy thought that perhaps Yab-gal was attempting to say something, but nothing intelligible was spoken. It was a marvel that the man made any sounds at all. The horrendous wound that opened Yab-gal's chest should have taken his life cleanly. Dak could not fathom how he had inflicted such damage to another human.

Dak had grown up around Yab-gal. The cupbearer was always by his father's side, and the boy knew the man and his family well. Ap'kalloo and the others who tried to kill Dak were vassal kings who governed neighboring lands, but these men were not strangers either. They had been mentors, and some were relatives through marriage. In many ways, the five who accompanied him and his father on his first boar hunt were like family. They each were so quick to aid in grooming Dak as the prince and future ruler of his father's kingdom. The cut from their betrayal went deep, and the spear began to quaver in Dak's hands while he stood in the flood of memories he had with Yab-gal. He recalled the jokes they shared in the great hall, the pranks he pulled on his father's cupbearer, and playing with his son in the cool parts of the day.

His son. Yab-gal had a son. A son named Ku'le. Ku'le was only a little younger than Dak; just a few months from going on his own first boar hunt. But Dak had taken that rite of passage away from his friend. Ku'le and his father would never plan a hunt together. Yab-gal would never see his son again.

The weight of the spear was too much for his grasp, and it fell to the ground. Dak took one step towards Yab-gal and went to his knees while tears poured out from his eyes. He grabbed the hand of his father's cupbearer– his father's betrayer– and held it tight to his chest. Yab-gal still couldn't turn towards Dak, but the timbre of his dying breaths changed. Tears mingled with the man's spittle and blood in which he lay. Something like a whimper came from deep within Yab-gal's throat. His condition forbade him from weeping with regret, but Dak could feel the sorrow in the man's cold, trembling hands.

YAB-GAL’S LIFE LINGERED ABOUT HIS BODY FOR AN HOUR. The dogs were drunk from the boar's blood and drowsy with bellies full of flesh when Dak let go of the man's hand. None of the others around him stirred while he comforted Yab-gal to the veil of death. Their life-strings had been severed cleanly, while the cupbearer's frayed before finally breaking.

Blood and earth clung to the hem of Dak's tunic. Never again would it be the same color as before. Much like Dak's soul, the fabric had been tarnished by violence and stained by death. He examined the garment. It was a fine tunic, tightly woven and embroidered with a pattern that only royalty could afford to wear so casually. He was a fool to wear such good clothing on a hunt. His own father, the king of the richest lands in all the world, girded himself that morning in a simple, threadbare smock. His own father, the king of the richest lands in all the world, had died in a pauper's attire.

Dak tore at the soiled tunic. The fabric refused to yield to his rage and held tight; his hands grasped and slipped away without splitting a single seam. He screamed. It wasn't the cry of a warrior, or even that of a man. His gasping wail sounded more like it came from a baby with an Adam's apple than a boy at the cusp of manhood. He tore at the grass, broke his nails against rocks underneath the soil, and screamed again. Then he wrenched his clothes once more and kicked at the bodies on the ground. Bastards, all of them, he thought. Cowards, too.

UNSEEN BY DAK, a runner from the citadel approached the edge of the thicket with the subtlety of a snake amongst hens. He heard Dak's cries while he was still a long way off, and wondered what manner of tragedy might have befallen the hunting party to warrant such grievous sounds.

The runner had been sent by the queen so that she might hear a report on the hunt's progress. This was an unorthodox request made by her majesty, but the runner was not one to protest against his monarch and did as he was told. The hunters' tracks were easy enough to find: the seven men with the same number of hounds chasing after a wild boar left quite a path; only wood cutters might leave clearer tracks through the trees.

He came upon the thicket and saw Dak first. The boy was no longer screaming, but stood with his face in his hands. Bloody hands. Dak was smeared with blood. It was even thick in his hair, but there was no wound that the runner could see from where the blood might have come. That's when he noticed the others. Six men, including the king, lay dead on the ground. The dogs and the mangled body of a boar were not far off, but the runner knew better than to think that the beast was responsible for such carnage. Nor did his mind leap to conclude that Dak was the one who slaughtered the others. The runner's job was to carry messages, not interpret their meanings. The queen wanted to know how the hunt was progressing. He could now report that the hunt was successful, but also that the king was dead.

Copyright © 2025, Corey D. Evans. All rights reserved.